|

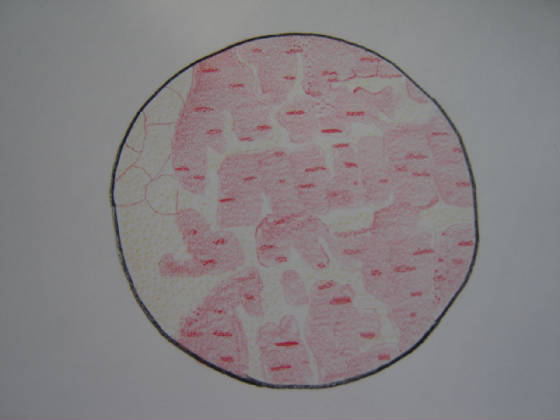

Most of the muscles in the human body are striated, or skeletal muscles. They get the name ‘striated

muscle’ because of the light and dark striations, or bands visible under a microscope; and ‘skeletal muscle’

because most are attacked to the skeleton by tendons. These tendons usually occur in pairs, each pulling in the opposite direction.

Striated muscles are controlled voluntarily and consciously, and give the body its general shape. Most muscles contract similarily,

however, are classified at either phasic (fast twitch) or tonic (slow twitch), which distinguishes between the time length

required for a muscle to move in response to stimulus. Striated muscles are usually considered phasic. Comprised of many cylindrical

bundles of cells enclosed in a sheath known as the sarcolemma, striated muscles are considered phasic. Each muscle fibre of

a striated muscle consists of several hundred to several thousand of myofibrils, which are tightly packed strands. Each myofibril

is composed of alternating filaments made up of actin and myosin (both proteins), which interact before a muscle contraction

and produce actomyosin, a contractile material. The stimulus for muscle fibre contraction is in the form of an electrical

impulse from the nervous system, which allows movements within the body.

|